CNN

–

For most of her life, Vivian Maier was something of a mystery. Her photographic talent was not recognized because she kept her work a secret from most people who knew her, including the New York and Chicago families for whom she worked as a nanny and caretaker. Maier printed only a small fraction of the hundreds of thousands of images of vibrant city life she shot with her Rolleiflex and Leica cameras over nearly five decades, and showed them to almost no one, instead amassing boxes and boxes of negatives. and raw films.

Her fame came posthumously, and only because the contents of her Chicago closets were auctioned off in 2007 after she stopped paying rent.

“Vivian Maier mystery, discovery and work – these three parts together are hard to separate,” said Anne Morin, curator of the touring exhibition Vivian Maier: Invisible Work, which opened on May 31 at Fotografiska New York, US Post of the Swedish Museum of Contemporary Photography.

The show, which runs until September 29, does not attempt to solve the mystery of Maier’s life, but instead focuses on the work itself, with more than 200 photographs on display, including around 50 vintage prints made by Mayer. Morin places her work on par with that of renowned street photographers such as Robert Frank and Diane Arbus, and worthy of a place in photography history. “No one doubts that,” Morin told CNN. “The work is solid and Maier had a great eye. And in 10 years, we can do another completely different show – she has more than enough material to bring to the table.”

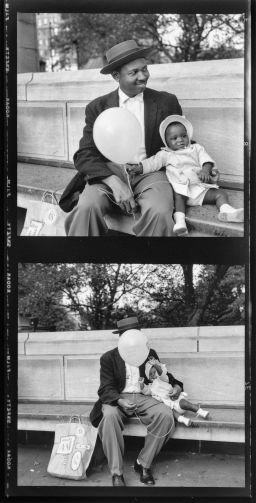

The exhibition is also a homecoming of sorts for Maier, who was born in New York to a family of French and German immigrants. She began capturing city street scenes as a young woman in the 1950s, first borrowing her mother’s Kodak Brownie box camera and then purchasing her professional-grade Rollieflex, which she taught herself to use. Her confidence and skill in finding the right moment to snap the shutter is evident even in these early works, in which Maier based herself on the unique characters and situations that make up city life: Men snoring open-mouthed on park benches; a balloon from the Central Park Zoo floats up to hide the face of an overjoyed father as his child approaches him.

But while Maier was known to use commercial studios in New York to process her film, she never seems to have made a serious effort to exhibit or sell her work. Maier’s return to New York as a popular icon is “a big thing not only for women, but for all artists who work and are never recognized and never have the opportunity to be seen, to be shared, to exist,” Morin. said. “It’s never too late to repair history.”

New York is “in many ways the heart of the history of photography in America,” said Sophie Wright, the museum’s director. “So now it’s amazing to be in a position to bring Vivian back into that world. She is a rediscovered and important voice of the 20sth– the picture of the century.” Wright added that Maier’s photographs are made with “so much thought and care and a lack of self-awareness — no audience in mind. In a way, it’s pure, artistic expression for him.”

Maier’s name and work first captured the public imagination in 2009, the same year she died in Chicago, after collector and amateur historian John Maloof shared scans of her work on the photo-sharing website Flickr. He was looking for advice on what to do with the thousands of negatives, prints and undeveloped rolls of film he had acquired over the past two years after stumbling upon Maier’s work at her storage cabinet auctions.

Photographers and critics immediately noticed Maier’s well-balanced compositions, and her incisive and often humorous view of the people and places she encountered, not only in New York but also in Chicago, where she moved in 1956 and spent most of her adult life. as well as the far-flung places she visited on vacation, from California to Europe and Asia. In 2011, Maloof published a book, Vivian Maier: Street Photographer, and with filmmaker Charlie Siskel co-directed the 2013 documentary Finding Vivian Maier, which was nominated for an Academy Award.

A number of other gallery shows and biographies have also debuted in the years since — as well as a legal battle over Maier’s estate, which is now overseen by Chicago’s Cook County Probate Court, and which Maloof has signed an agreement to display and sell that work. (While Maier had no children of her own to inherit her fortune, 10 potential heirs in Europe have been found in her extended family, and the court is considering whether her brother Carl, who died in a psychiatric hospital in 1977, could However, the public’s appetite for Maier has not waned. When the current exhibition was exhibited at the Musée du Luxembourg in 2021, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, more than 213,000 people attended during its four-month run opening in New York on May 30 had over 600 visitors.

Despite her immense popularity, some museums have been slow to accept her work, even those with large photography collections. Wright attributes this caution to Maier’s work to the fact that she did not make many prints herself. “There’s a reserve to be seen as pushing a narrative about the work that isn’t the artist’s,” she explained, as well as a nervousness about the politics of her situation as a woman who was vulnerable in her later years. (Toward the end of her life, after her hoarding led to her losing her job as a nanny, Maier was believed to be facing homelessness until two of her former charges, Lane and Matthew Gensburg, paid for an apartment for her to live in. lived in and later a nursing home.)

Maloof and photography dealer Howard Greenberg, who represents his extensive collection, acknowledge concerns about the posthumous printing of Maier’s work and, speaking at the exhibition’s opening, said it led to their decision to create only reproductions of untouched, direct by its negatives. In the show, there are many instances where these later prints appear next to Maier’s own, showing how she chose to focus on certain elements in a scene.

Maier’s presence can also be felt in the exhibition through the audio recordings she made of interviewing the children she cared for to encourage their critical thinking, which were also found in her storage cabinets. They are played in all the galleries. But the most persistent memories of the artist behind these works are the many self-portraits she made, often as reflections on mirrored surfaces and glass, or simply as her own shadow cast on the ground or wall.

“The beating heart of the work is self-representation,” Morin said, and it’s these works that she finds resonate most with today’s audiences. “Everybody says, ‘Oh, my God, Vivian was the godmother of the selfie.’ But it is different”, continued the curator. Maier’s self-portraits are a stubborn insistence on declaring her independence and identity, at a time when women, and especially domestic workers like her, were ignored and marginalized. “She wanted to record it,” Morin said, imagining Maier saying, “I’m here in this moment. Nobody’s going to wipe my face. I exist and I have proof.”

#Vivian #Maier #Mysterious #York #Nanny #Helped #Shape #20th #Century #Street #Photography

Image Source : www.cnn.com